A Deeper Look at Sex with Tara Isabella Burton

- Aug 9, 2021

- 6 min read

“I wanted to outrun the Nothing. There was nothing I would not have sacrificed—friendships, relationships, the blood from the heel of my foot—to get it. I sacrificed all of myself. I emptied myself out. I hit bottom, in a thousand different ways, and got what I wanted, in a thousand more, and then, somewhere in the middle of my seeking a vague and generic sense of Poetry, I found a specific one.

One rooted not in a vague sense that magic was real and that the world could at any time be an enchanted one, but in a concrete sense that at one particular place, at one particular time, the laws of nature had been suspended…

The faith I found proclaimed a sanctified world, and a redeemed one—an enchanted world, if you want to call it that—but one where meanings were concrete. It offered me not just a sense of emotional intensity, but a direction in which to channel it. It contained magic not for the sake of magic, but rather miracle for the sake of goodness. God died and came back from the dead not because magic was real, but because love was stronger than an unmagical world.” — Tara Isabella Burton

Every thought leader is influenced by other thought leaders. When I wrote The New Copernicans I mentioned three: Charles Taylor, Iain McGilchrist, and Lesslie Newbigin. Today I am closely following three additional thought leaders, two of whom have immanent forthcoming books. These three are James K.A. Smith, Iain McGilchrist, and Tara Isabella Burton.

James K.A. Smith is a professor of philosophy at Calvin University and editor of Image Journal. He is a clear and deep writer who regularly engages broader cultural questions. His book on Augustine’s spiritual pilgrimage is well worth one’s attention: On the Road with Saint Augustine: A Real-World Spirituality for Restless Hearts. I resonate with Smith because he is theologically a charismatically-influenced Kuyperian, a critic of Enlightenment modernism, and phenomenologically-oriented philosophically. As a student of Peter Berger and James Davison Hunter, my own sociological orientation is influenced by phenomenological sociology. I was, of course, heartened that Smith gave a chapter to French social theorist Pierre Bourdieu, on whom I did my dissertation, in his book Imagine the Kingdom: How Worship Works. In personal conversations with him, I also discovered that he too is reading the work of Iain McGilchrist closely. I consider Smith my closest intellectual mentor. So it is with great anticipation that I am awaiting the forthcoming publication of his new academic book, The Nicene Option: An Incarnational Phenomenology (Baylor University Press).

Almost equal to Smith in my thinking is the work of Iain McGilchrist, who is best known for his book The Master and his Emissary. This is a seminal work and I hope he will soon be considered for The Templeton Prize. The public academic knock on McGilchrist is that he is “a one-trick pony.” This critique will soon be dissolved by the publication this fall of his new book The Matter With Things. It is a book on epistemology and metaphysics. The Matter With Things, which is due for publication in October 2021, by Penguin Random House. This book may well place him among the leading thinkers of our time.

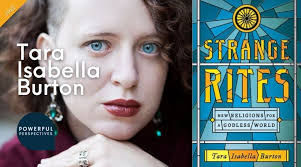

The third current influence is that of Tara Isabella Burton. As a student of “religious nones” and the “spiritual but not religious,” I was intrigued by her book Strange Rites: New Religions for Godless World, which I reviewed for Critique. She observes, “I think that traditional conceptions of secularization in America have looked at the religiously unaffiliated as an indicator that America is getting less religious. That is actually not the case. About 72 percent of the religiously unaffiliated say they believe in some sort of higher power. About 17 percent say they believe in the Judeo-Christian god. In addition, you have people who affiliate with religious tradition—i.e., self-identified Christians—whose belief systems, structures, practices, and rituals are a little bit more eclectic. Almost 30 percent of self-identified Christians, for example, say they believe in reincarnation, which traditionally would not be something you would associate with orthodox Christian doctrine.”

Since the writing of this book, Burton has come to a genuine faith and has begun integrating her keen cultural insights with her relationship with Jesus. Among those who are taking her seriously is Anne Snyder at Comment magazine. Burton has not written widely on her personal conversion and she may not so that she can maintain her close ties with her New York bohemian literary world. This same approach was taken by French philosopher Simone Weil on behalf of her communist friends. Burton is brilliant and her Oxford theology doctorate is evident in both her rich vocabulary, breadth of reading, and prescient insights. Burton is “one of our most profound thinkers on the 21st century’s search for religious meaning.”

I was taken with her recent Comment article, “Beyond Sexual Capitalism: The Christian’s Invitation." This article is the subject of this post. The personal background to this article is revealed in her earlier Commonweal article, “Bad Traditionalism." She is not a darling role model of the evangelical purity culture, but is by her own admission “a queer woman, theologically orthodox, and politically progressive.” She is the poster child of new Copernican Christian spirituality. When she speaks, I listen.

Burton acknowledges along with SUNY Albany sociologist Steven Seidman that our understanding of sexual intimacy today is divided between two competing camps (“Contesting the Moral Boundaries of Eros”). Americans, he writes, are divided between two different moral logics when it comes to intimacy: “morality of the sex act” logic and “communicative sexual ethic.” One viewpoint assumes that sex is connected to the cosmos, having an ontological relationship to the nature of reality. The other views sex as merely a decision between two consenting adults.

One orient sex vertically and the other horizontally. Mila Kunis commented on her film “Friends with Benefits,” “Having friends with benefits is a lot like communism. It works well in theory, but not so well in execution.” It’s a practice that is not aligned cosmologically with reality. This is a traditionalist perspective. In contrast, Science Mike (AKA Mike McHargue) and his compatriots on the Liturgist podcast had an episode entitled, “The Ethics of Fucking.” There was nothing intrinsically sacred about sex from their perspective, only the ethics of consent. These two viewpoints are not a contrast between those who are Christians and those who are not. For many Christian young people today, particularly those attracted to a progressive Christianity, adopt a consent view of sexuality. For them the choice of cohabitation outside of marriage is a totally consistent understanding of their faith and sexuality.

What makes Burton’s article so interesting is that she takes her critique one step deeper than these two camps to ask how our sexual imagination has been damaged by our cultural imagination. She writes, “To understand disordered sex merely as a sin of untrammeled physical appetite, on par with, say, gluttony, is to misunderstand both sin and sex. Broken sex is downstream of broken culture: the broken way we relate to one another, and the broken way we understand ourselves.”

In her critique, she finds both the Christian traditionalist and progressive view of sexuality wanting. “Both visions of Christian sexual ethics are insufficient, because both fail to treat sexual sin as the inevitable culmination, in our most intimate spaces, of the broken way we exist with one another.” In short, we use sex as a consumer product, as an exchange of value, or worse as an expression of power. “It is a mistake either to assume, as many traditionalists do, that the right social or even religious institutions can automatically redeem our animalistic sexual urges, or to assume, as do many Christian progressives, that sexual desire is purely a matter of private affective exchange.... The greatest sexual sins do not derive from our animal instincts, but from our cultural ones.” These are the cultural patterns reinforced by the pornography industry, dating apps, and reality TV shows. It is found in “every capitalistic exchange that treats human beings as currency, that treats human love and attention as commodities, that treats sexual or romantic gratification as boosters for our own self-esteem.” In short, traditionalists may not condone porn, while still adopting a porn mindset in their intimate relationships. The viewers of The Batchelor are just as guilty as those who view PornHub as both work from the same relational premise. What a consumerist view of sex does to sexuality is make genuine love impossible. Burton concludes, “We would do better to speak of a collective lack of faith: in our inability to love one another, and ourselves, as God loves us: not as means to an end, not as notches on a bedpost, not as rewards for disciplined behavior, but as we truly are.”

Before we have a sexual problem, we have a cultural one. As Burton puts it, sexual sin has “less to do with how we touch one another than how we see.” Consumerism as an ethos leads to an onanistic relational narcissism not to genuine self-giving and love. Our problems are deeper than we even realized. To love like Jesus truly demands more.

FYI—Burton is working on a history of self-creation to be published by Public Affairs in 2023.

กำลังมองหาความรักหรือมิตรภาพใหม่ๆ ที่เข้าใจคุณจริงๆ อยู่หรือเปล่า? Fiwfan คือแอปหาคู่ออนไลน์ที่ออกแบบมาเพื่อให้คุณสามารถพบปะพูดคุยกับผู้คนที่มีความชอบคล้ายกันได้อย่างง่ายดาย ปลอดภัย และเป็นกันเอง พร้อมระบบจับคู่ที่แม่นยำและใช้งานสะดวกทุกที่ทุกเวลา เปิดประสบการณ์ใหม่ในการหาคู่ผ่าน ไซด์ไลน์-fiwfan ที่จะพาคุณไปพบผู้คนหลากหลายสไตล์ สร้างความสัมพันธ์ที่ตรงใจ และเติมเต็มความสุขให้ชีวิตคุณอย่างน่าประทับใจไม่รู้ลืม